As I’ve said in the past, action scenes are usually what starts me on a writing project, or what gets me out of being stuck. But how do ‘action scenes’ work anyway?

Action scenes are often more about emotion than physical action. Putting my characters through the emotional wringer is a great way to break up the log jam in my head. I may not end up using the scene, but like everything else I write, these scenes will inform something else, even if it’s just what my state of mind was at the time I wrote them.

I can hear some people saying, “Okay, okay, I get what you’re saying, but you said this was about action scenes. Can we get back to that?” Sure.

Why do guys love war movies? Is it because we get to see sh*t blown up? Yes. Do we get to see the good guys kick the ass of the bad guys? Yes. But I think there is something more going on behind the scenes. Don’t worry, this ties directly to the subject of action scenes. War movies make us guys – feel.

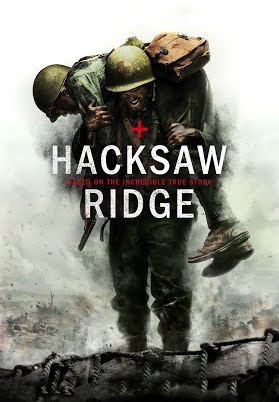

A great example of this is the movie Hacksaw Ridge. This isn’t the normal war movie narrative, about killing the bad guys or taking ground. It hits us in the guts because it’s about Desmond Doss, a guy who refused to carry a gun, but still served on the front lines of World War II and saved lives.

Camaraderie, loss, victory, etc, etc; war movies get our heart’s pumping in a lot of different ways. They are a place where we’re it’s acceptable for us guys to have strong emotional responses. Now, I’m speaking for myself and from my generation and I know a lot of guys out there are much more tuned into their emotions than some of us.

Actions scenes need to work the same way war movies do. There have to be kick-in-the-guts emotions running through them or they are just stage direction. Who gives a damn that our protagonist is strong and fast if we don’t feel the risk to them, if we don’t feel their fear and uncertrainty, if we aren’t entrenched in the reason they are fighting? In my opinion that is the key to action scenes.

A good example of an emotionally driven action scene is the duel between Achilles and Hector from the film Troy. Achilles’ fury at Hector for killing his cousin would have have been far less powerful without the counterpoint of Hector having been shown as an empathetic character earlier on. As a result of these clashing points of view the crescendo fight scene is a seething display of emotion.

Yes, there are technical pieces in all action scenes; punches, kicks, gunshots and sword blows, but if the action is driven by emotion, the details of the fight become less important. After all, what is the reader really there for? Sure, some readers want the technical nitty-gritty, and that’s great. But for most people they are (hopefully) invested in the character who is in the fight, like Hector above, and so they want to -feel- along with them. In narrative writing, we don’t have the advantage of a stirring soundtrack or stunning visuals to get our emotions ramped up, we have words. Now, the other side of this conversation is that we have ‘lots of words’ to tell the story with, to give wonderful description. With words the reader can smell the distant flowers and trees, taste the dust and sweat and feel the heat of the sun. But we still have to get the most punch in the fewest number of words.

Conflict on every page. That’s a common thing most writers are taught. In an action scene, it has to be reduced to surgical precision. Every breath and action must carry all the emotional weight while moving lightning fast. If it drags, the reader becomes distracted. Too much detail, the reader loses the flow of the action. And so on and so on. I’ll often punctuate my action scenes with short ‘punch sentences.’ These punch sentences can be just a few words, but they imbue the action with rapidity and a feeling of stop and start motion – in other words, action.

In this example, from ‘The Tomahawk Incident,’ things are happening fast, there is confusion, self-recrimination and assessment, all occurring at the same time.

“The lightkeeper’s eyes suddenly went wide. “LOOK OUT!”

A powerful swing of his staff sent Katja tumbling. When she looked back over her shoulder, he was falling. The lightkeeper crashed to the sidewalk with a sharp cry of dismay and pain as a tall, severe-looking woman lunged past him.

Katja saw the outline of the long knife in the woman’s hand. Her mind caught. She’d allowed thoughts of David to block her awareness of her surroundings. But her body reacted instinctively, before she could think, bringing her attaché up like a shield. The point of the dagger slammed into the paper-filled leather case. Katja twisted it hard and threw the case aside, pushing up to her feet from the bricks. All thoughts of David vanished as the nondescript woman pivoted, following the motion and dislodged the knife. Katja hadn’t realized she’d grabbed the collapsed baton at her belt through the opening in her overcoat until the weapon snagged. She gripped her coat and yanked. The baton came free with a pop of stitches. The knurled grip in her hand and familiar Snap! as she threw her arm downward to extend it focused her.”

There’s a lot happening here and there should be. Action is about chaos, but chaos the reader can (hopefully) easily follow.

The other thing that makes action work is that the reader has to be invested in someone or something involved in what’s happening. The someone could be our hero in danger such as Hector in Troy above, or someone attached to them such as Lois Lain being thrown off of a rooftop that Superman has to save – again. The ‘thing’ could be a vial of serum that’s going to save the world that our hero is lunging after before it rolls off the edge of a cliff.

Action is part of the narrative. In film, fight choreography is carefully crafted to fit the story that’s being told. Like a fight scene in a book, every breath and action as well as each camera angle and the way shots are edited together combine to hopefully enhance the story. This works better and worse depending on the film. Let’s look at the Bourne Identity. Action all over the place, but in service of the overall story of our amnesiac ex-assassin. In this clip, we can clearly see the character’s surprise and revelation about his capabilities. This is the first time we see what Bourne is capable of. That’s why the scene is there and the character’s emotions are what make it work.

And this is what that whole fight scene looks like in (a version) of the script:

“COP #2 has heard enough —

giving a sharp poke with the nightstick — into THE MAN’s back — and that’s the last thing he’ll remember because —

THE MAN is in motion.

A single turn — spinning — catching COP #2 completely off guard — the heel of his hand driving up into the guy’s throat and —

COP #1 — behind him — trying to reach for his pistol, but THE MAN — still turning — all his weight moving in a single fluid attack — a sweeping kick and —

COP #1 — he’s falling — catching the bench — trying to fight back but — THE MAN — like a machine — just unbelievably fast — three jackhammer punches — down-down- down and — COP #1 — head slammed into the bench — blood spraying from his nose — he’s out cold and —

COP #2 — writhing on the ground — gasping for air — struggling with his holster — THE MAN — his foot — down — like a vise — onto COP #2’s arm — shattering the bone — COP #2 starting to scream, and then silenced because —

THE MAN — he’s got the pistol — so fucking fast — he’s got it right up against COP #2’s forehead — right on the edge of pulling the trigger — he is, he’s gonna shoot him –“

Obviously, writing action in a screenplay and in a novel are radically different, but what I’m aiming at is still there. Action in service to the story.

Action = Emotion. Rage, terror and even dispassion. In ‘The Silence of the Lambs’ Hannibal Lecter viciously attacks his guards. We learn earlier on that ‘his pulse never got above eighty-five’ while he was committing some awful act. In the case of attacking his guards: ‘Dr. Lecter’s pulse was elevated to more than one hundred by the exercise, but quickly slowed to normal.’ His lack of emotion is the dark mirror of the terror and powerlessness of his victims, making it that much more frightening. And that tension gives the scene its impact.

COMMENTs:

0